The Origins of the Mass Ave Cultural Arts District

By Jeffrey Stroebel for the Massachusetts Avenue Cultural Arts District

The Mass Ave Cultural Arts District (MACAD) is a nonprofit public benefit corporation founded in 2021 by residents, cultural arts organizations, businesses, and property owners. It supports those who live, work, play, perform, create, and invest in the Massachusetts Avenue community through initiatives focused on urban placemaking, historic preservation, walkability, arts, inclusiveness and equity, community celebrations, and advocacy.

Cooperation for the Common Good

In April of 1909, eleven merchants joined together to incorporate the Massachusetts Avenue Merchants’ Association. Their goal was to attract trade to the area and foster “more enlarged and friendly intercourse” between merchants of the district. An initiation fee of $5 was charged along with $5 in annual dues. The founders represented both the larger and small businesses on the avenue and most were well-known businessmen in the city. The first board of directors was made up of J. Howard Amos (Ralston Boot Co), Robert C. Bennett (R C Bennett & Co Clothing), John Bettermann (Bettermann Brothers Flowers), O.J. Conrad (Conrad Clothing & Cloaks), Leonard Geiger (Geiger Confectionary), George J. Hammel (Hammel Grocery), Robert H Losey (Buick-Losey Motor Co), George J Marott (Marott Department Store), Herbert H. Reiner (Reiner Fine Furs & Skins), Harry Stout (Stout’s Factory Shoe Store), and Gustav H. Westing (G H Westing Co Bicycles, Motorcycles and Sporting Goods). Marott was elected the first president, Conrad vice-president, with Westing to serve as secretary, and Stout as treasurer. 1

These businesses represented only a portion of today’s Massachusetts Avenue, consisting of only three blocks from the intersection with Pennsylvania to the south up to the German House (Athenaeum) at Michigan Street to the north (the avenue was constricted in the 1970s with the construction of the now Regions Bank Building, which obliterated the first of these three blocks). This lower portion of the avenue contained most of its retail businesses as the avenue became more residential and eventually industrial as it stretched beyond College Avenue.

An Era of Growth and Prosperity

Even prior to the founding of the merchant’s association, the avenue was experiencing a period of growth and prosperity. As the city continued to expand, and with street car traffic constantly streaming up and down at rate of every two minutes, by 1906 an estimated twenty thousand people passed through the avenue daily 2. In addition, the avenue continued to supply the growing adjacent neighborhoods, such as Chatham Arch and Lockerbie, whose residents could easily walk to the stores. Crowded with street cars, wagons, carriages, and thousands of pedestrians, the avenue was one of the busiest streets in the city. In 1906, the Indianapolis Star contained a two page advertisement promoting the avenue: “By the deep faith of a certain clans of merchants who had foresight, backed by a little money, and who believed that the city of Indianapolis could spread more easily to the northeast than any other direction, a foundation of mercantile houses was laid, which in ten years more will probably change the business geography of Indianapolis to a marked extent.” The advertisement cited cheaper rents as a significant advantage over the more established Washington Street businesses and emphasized that these savings were passed directly to consumers: “Prices are lower on Massachusetts avenue, while the quality is the same.” 3

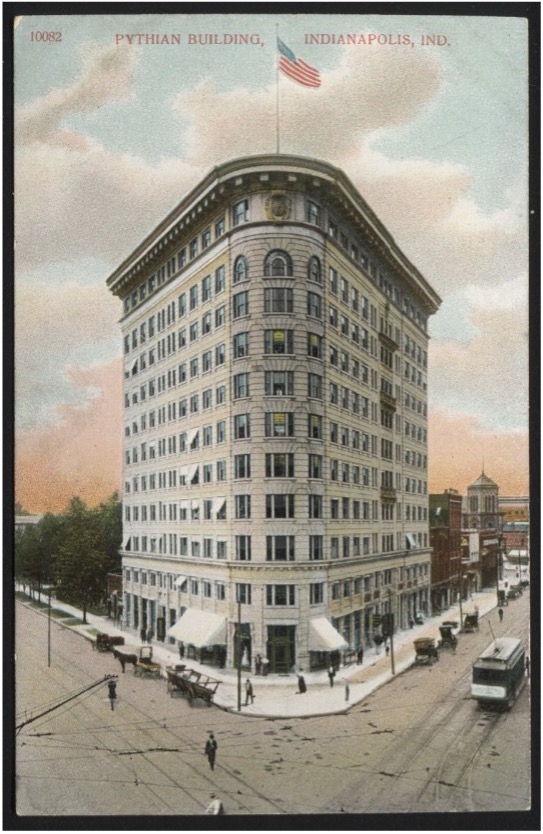

The 1907 completion of the eleven-story, stone-and-terra cotta, Neoclassical Revival-style Knights of Pythias building at the intersection of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania created a stunning gateway to the avenue from the city center. Designed by Rubush and Hunter, it was the second-largest flatiron building in the country behind Daniel Burnham’s Flatiron Building in New York City, and for a brief period, it also was Indianapolis’ tallest building.

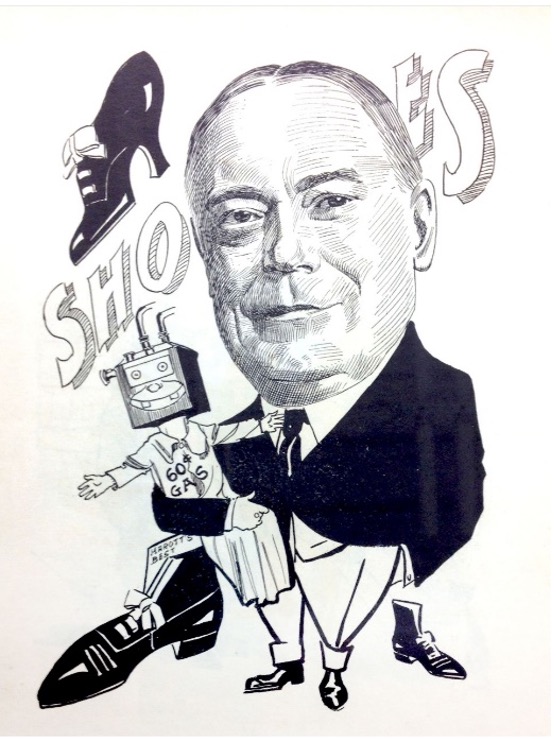

George J Marott

That George J Marott emerged as the leader of the new merchant’s association was no surprise. Born in Daventry England, about thirty miles east of Stratford-upon-Avon, Marott emigrated to the U.S. with his parents in 1875 at age 16. His father, George P Marott, quickly established a successful shoe store at 16 North Pennsylvania. Young George worked for his father before creating his own business in 1884. At age 26, he formed the George J Marott Company with $167 of his savings and $168.25 he borrowed against his personal furniture, including a piano he had previously purchased for his new bride. He later told the Indianapolis Star, “I asked Mrs. Marott if I could place a chattel mortgage on the piano. She lifted her apron to her eyes and cried but told me to go ahead.” Marott also attracted investors, enabling him to stock his store with $2,000 worth of merchandise. Soon, his store on East Washington Street was regarded as one of the largest and most attractive shoe stores in the country. 4

George J. Marrot

Marott proved to be an outstanding businessman. Despite a severe economic depression in the 1890s, Marott expanded his business and acquired others, amassing large holdings in interurban companies, utilities, and commercial real estate. He owned the Indiana Railways and Light Company, and in 1905 founded Indianapolis’ Citizens Gas Company.

In the early years of the new century, Marott recognized the opportunity present on Massachusetts Avenue. He saw an avenue that was “throb[bing] every hour of the day with a mass of humanity that foretells its future greatness.” Eager to seize this opportunity, in 1905 he began construction of an ambitious five-story with basement commercial building at the site of the old Enterprise Hotel in the 300 block of the avenue, just east of Harry Stout’s shoe store. Unfortunately, Marott’s vision of partnering with a large department store failed to materialize. As the building sat empty, observers began to refer to it as “Marott’s White Elephant.” After two years of waiting, Marott decided to occupy the building himself. The Marott Department Store Company opened to much fanfare on October 1, 1908, with an estimated 65,000 people arriving to shop on opening day. Boasting “The Best at the Price, No Matter What the Price,” the enterprise was immediately deemed a great success 5. Marott was masterful in promoting his store with special sales, contests, and celebrity guests. For example, in January 1913 The Indianapolis News heralded a visit from “the most beautiful working girl in Chicago.” Beauty Queen Miss Rae Potter and her five assistants appeared daily for a week, demonstrating “toilet preparations that would assist women in improving their appearance by scientific methods.” 6

The Most Vibrant Commercial Area in the City

With so many factors present for success, the association quickly grew, reaching over thirty members within its first six months in 1909 7. In its early meetings, it sought greater illumination of the first three blocks of the avenue and the permanent assignment of a corner policeman. This last request was quickly realized, with an officer stationed on the corner of Massachusetts and New York. Among his duties was the regulation of streetcar traffic when fireman at the nearby station responded to alarms. Later, a mounted officer was added to patrol the three blocks and a successful negotiation with the Indianapolis Traction and Terminal Company led to the laying of new track on the avenue and new pavement between the tracks. The association also asked for street sprinklings and sweepings to reduce the dirt and dust generated by streetcars and increasing automotive traffic 8.

One of the first events planned by the new association was a fall festival in late September of 1909 to mark the first anniversary of the opening of Marott’s grand department store. This opening was credited for an increase in interest in the avenue and boosting commerce for all businesses. Stores were festooned with 12×14 foot American flags and decorated inside and outside for the occasion. A festive fall opening soon became a tradition, with Marott offering cash prizes of $20, $10, and $5 for the best window decorations. At Christmas, the lower avenue from Pennsylvania to Alabama was decorated by stringing 2,500 feet of electric lights and affixing holly to the wires on both sides of the street 9. The following year, the merchant’s association hired men attired in military style uniforms to serve as advertisers. Stationed at corners during the fall opening period, the agents, wearing bright red caps and suits with gold trimmings, greeted potential customers and distributed cards advertising the stores on the avenue 10.

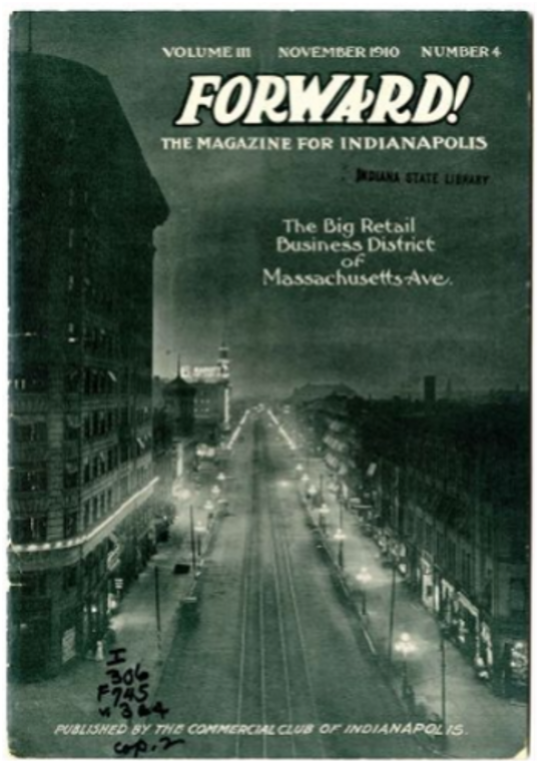

By 1910, Massachusetts Avenue was becoming recognized as the most vibrant commercial area in the city. The Commercial Club of Indianapolis (a precursor to the Chamber of Commerce) featured the avenue as the cover story in its November 1910 publication Forward! The Magazine for Indianapolis, proclaiming “The Big Business District of Massachusetts Ave.” The cover shows an evening photograph of the avenue looking from the Pythias building in the foreground past the brightly lit 208-foot tower of the newly constructed Murat Temple. The avenue is tidy, well-illuminated, with a set of street car tracks extending down the center of the broad street 11. “Massachusetts avenue has ‘caught on,’” proclaims the article. “It has become a business center—a retail district. Men have made it so by their progressiveness and their aggressiveness. They have a saying, ‘If you can buy it in Indianapolis, you can buy it on Massachusetts avenue,’ and they back it with the goods.”

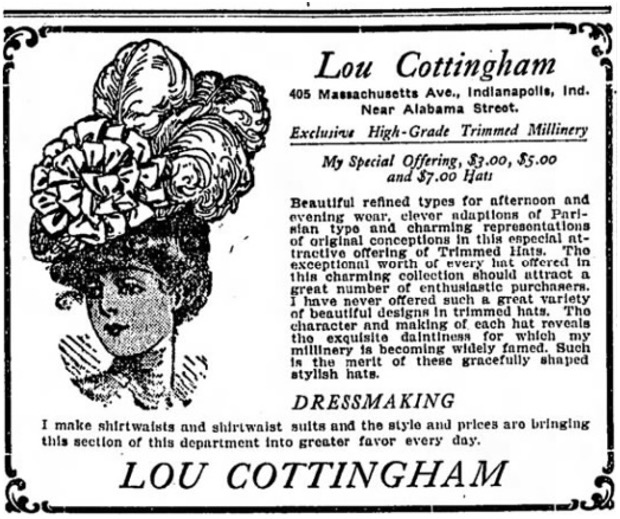

The merchant’s association ran a full-page advertisement in Forward, listing 32 members. These businesses represented the tremendous commercial diversity contained within only three blocks. There were three clothing stores, three automobile dealers, two bicycle shops, two cleaners and dyers, two drug stores, two groceries, a large department store (Marott’s), a store selling artificial limbs, a bakery, candy store, creamery, flower shop, fur shop, hardware store, hat store, jeweler, milliner, paint, a glass, and oils store, sporting goods store, undertaker, and wall paper store. Of these 32 businesses, only one was owned by a woman. Lou (for Lulu) Cottingham was a 48-year-old milliner, originally from Kokomo, who had sold fine hats on the bottom floor of the Oxford Building at 405 since 1906. Milliners occupied high status among the city’s working women, and Cottingham established a successful business selling adaptions of Parisian style ladies’ hats. She was also a seamstress, making shirtwaists and ladies suits.

The spring opening of 1911 was marked by large blue banners bearing the words “Spring Opening” in white letters. Bargains were featured in almost all the stores and advertised through colorful window displays. The Indianapolis Star reported that crowds invaded the avenue and hundreds of shoppers thronged the stores: “Altogether it was an unusual event, typical of the unique association of the Massachusetts avenue merchants.” Trading was described as brisk with “a small army of women laden with armfuls of packages walking up and down the avenue 12.

Challenges of Growth and the Impact of the Automobile

Unfortunately, the exuberance of 1909-11 was short-lived. The quick prosperity mitigated one of the avenue’s original advantages. Property values quickly increased, and rents doubled. Of the 32 members listed in the Forward publication of 1910, only seven were still in business on the avenue a decade later. There are several possible explanations. The businesses on Massachusetts Avenue tended to be small and proprietor driven. Maintaining stable, decades-long businesses of this type is always difficult. The character of the avenue was changing as automobiles became more popular. This dispersed housing patterns as upper-and middle-class patrons moved further from downtown. Travel to the shops was no longer primarily on foot or by streetcar but rather by automobile.

With broad sidewalks and two lines for streetcars running down the middle, the avenue left little room for automobile traffic and parking. Proposals to widen the avenue were advanced as early as 1920, but action was stymied over disputes as to how to fund the project. Rarely a week passed between 1910-1930 without some report of a vehicular accident. Streetcars hit pedestrians and automobiles, automobiles struck pedestrians and other autos, and the avenue was increasingly being viewed as over congested and unsafe 13. The congestion impacted the ability of firefighters located at the station at New York and Massachusetts to respond to fires, and there were calls for relocating the station as early as 1910. Interurban freight cars were banned on the avenue during business hours in 1914, and the remaining passenger street cars were rerouted in 1916 in hopes of reducing the congestion in the lower two blocks. Unfortunately, each attempt at mitigation fell victim to the unstoppable tide of growing auto traffic.

The United States’ entrance into the World War in 1917 increased traffic from the city to Fort Benjamin Harrison, with Massachusetts Avenue being the main route, adding even more vehicular congestion. New traffic regulations in 1918 required parallel parking, banned left turns, and installed an eight-sided traffic semaphore at the confluence of Massachusetts, Delaware, and New York 14. In 1918, George Marott unsuccessfully proposed the city build four large, fire-proof municipal parking garages, with a total capacity of 10,000 spaces, financed by a $5-9 annual automobile licensing tax on vehicles seeking to park on the streets of the downtown business district. 15

Marott Departs

Even the most prominent business on the avenue could not escape the changing conditions. Marott discovered that low prices and a beautiful well-stocked store were not sufficient to sustain his success. In 1911, he purchased three Buick buses to ferry shoppers from the central business district to his department store and provided vouchers to customers who arrived via the interurban. Still, business declined, and in December 1913 Marott announced that he was going to sell the store to reduce his business holdings, commenting, “I like that business least of all.”16 Two months later, he sold his inventory and leased the building to a labor union syndicate planning to operate the store as a co-operative.

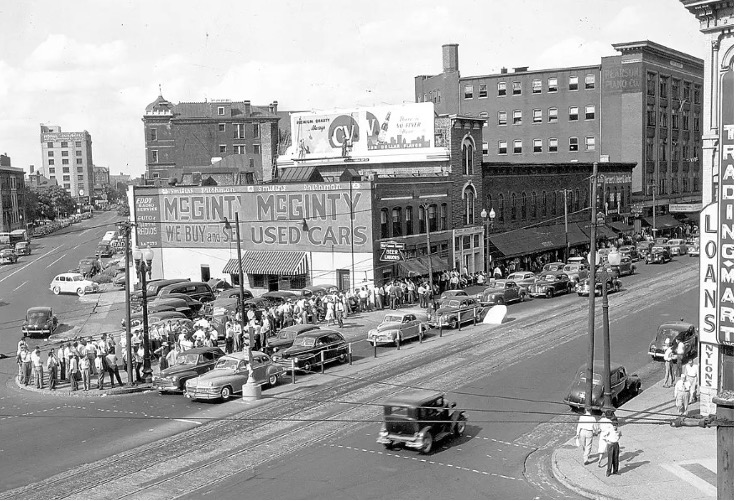

Men line up to register outside the Marion County Draft Headquarters at 342 Massachusetts Ave (far right) on August 30, 1948.

The Union Cooperative Department Store retained Marott’s store manager, Ernest S Phillips, and most of the sales staff but went out of business two years later, filing for bankruptcy in May 1915. Marott then purchased the store’s stocks and reopened in September, operating as The Marott Dry Goods Store.17 The fourth floor of the building was leased to the Red Cross and became a headquarters and warehouse for supplies donated throughout Indiana for relief in Europe.18 Marott sold the Dry Goods Store in the fall of 1919 to the United States Stores Company of which he was a stockholder. Under the new ownership, the store tried to revive the concept of a general department store and added a grocery in the basement.19 This effort failed, and in 1924 Marott decided to convert the empty store building into office space with a marble lobby and elevator service. Although he continued to own significant property on the avenue, he then set his sights further north, building the Marott Hotel at North Fall Creek Boulevard and Meridian Street. His Mass Ave building sat vacant until 1935 when it was finally leased by the U.S. Resettlement Administration, a New Deal agency that relocated struggling urban and rural families to communities planned by the federal government. In the 1940s, the building served as the Marion County military draft headquarters. Today, his building, known as the Marott Center is a commercial office building and hosts a restaurant on the first floor.20

As commerce expanded beyond the lower avenue, the original Massachusetts Avenue Merchants Association no longer represented the full scope of businesses on the avenue. In 1928, a broader successor organization was formed. Asa D. Chambers, a founder of the Bethard Wall Paper Company, was elected president. A new structure was adopted that provided for the selection of eight directors, each representing a block of the avenue, alternating between a tenant business and property holder on alternating blocks. The new association set out once again to address the traffic challenges.

By 1928, the avenue saw an estimated 14,500 automobiles, 2,235 streetcars, and 7,000 pedestrians pass between Ohio and Tenth Street every day. 21 Merchants consistently called for the widening of the avenue, but efforts stalled for more than a decade. There were two major points of contention, how much of the cost would be paid by merchant assessments and whether the objection of the Knights of Pythias could be overcome. The plans called for widening the avenue between Ohio and North streets from 55 to 66 feet. This required narrowing the broad sidewalks. The Knights, who occupied the largest and most prominent building on the avenue, were concerned that the widening would endanger the structural integrity of their basement. A frustrating series of approvals, reversals, and lawsuits ensued, and no action was taken on the widening throughout the 1920s.

Sears Comes to the Avenue

The character of the avenue changed dramatically in 1929 with the arrival of a Sears Roebuck and Company store at southeast corner of Alabama and Vermont. This store was part of the wave of 300 stores built by Sears, Roebuck & Company between 1925 and 1929 as it transitioned from being a mail-order-only retailer to one that offered customers both catalog-orders and physical stores. The Art Deco building, with a three-story tower to conceal its water tanks, included a soda fountain and luncheonette, tobacconist, millinery, infant department, and furniture. The basement offered tires, sporting goods, hardware, furnaces, paint, and even musical instruments. On July 25 1929, the mayor opened the main doors on Alabama Street to allow the first of an eventual 40,000 customers to enter on its opening day. 22 In 1940, a Sears Auto Center was added across the street, where the parking lot for Roberts Park United Methodist Church is located today.

The coming of Sears helped the merchant’s association finally achieve its goal of widening the avenue in 1931. Property owners eventually agreed to pay 40% of the costs and the Knights agreed to install bracing to their basement, which extended beneath the new street. The new, wider street narrowed the sidewalks and provided for two lanes of traffic on each side of the streetcar line and parking on the curb. 23

The Great Depression, World War II, and further migration to the suburbs would continue to bring changes to the Avenue. By the 1970s, it had fallen on hard times and was described as a “skid row.” Rejuvenation began in the 1980s and today, the avenue retains many elements of its first era of greatness between 1910-1930. It is a place of unique small businesses and host to a thriving arts culture.24

- “Would Improve Avenue.” Indianapolis Star. April 20, 1909, p. 3.

-

“Massachusetts Avenue: The Busy Growing Throughfare of Indianapolis.” Indianapolis Star. October 14, 1906, p. 22.

- Ibid, pp. 22-23.

-

“George J Marott 78 Today; Aware of Birthday, but ‘Hoped to Slip By’” Indianapolis Star December 10, 1936, p. 3.

- Ibid

- “Miss Potter Coming” Indianapolis News. January 18, 1913, p. 12.

- Indianapolis Star, April 25, 1909, p. 40.

- Indianapolis Star, April 28, 1909, p. 16.

- Indianapolis Star, December 14, 1909, p. 12.

- “Play ‘Boosting’ Parts in Avenue Open House,” Indianapolis Star. October 2, 1910. p, 27.

- Commercial Club of Indianapolis, Forward! The Magazine for Indianapolis. Vol III Number 4, November 1910.

- “Openings Attract Crowd. Indianapolis Star. 1 October 1911, p. 37.

- For an example of the many traffic injuries, see the account of the death of a woman in 1919. “Woman Killed Instantly.” Indianapolis Star. June 15, 1919, p. 7.

- “Traffic Rules Tried Out.” Indianapolis Star. July 23, 1918, p. 8.

- “Offers Aid In Parking Plan.” Indianapolis Star. September 1, 1918.

- “Gives Option for Sale of Department Store.” The Indianapolis News. December 27, 1913, p. 7.

- “Stockholders’ Interests Bought by Geo. J. Marott.” The Indianapolis News. August 30, 1916, p. 8.

- Indianapolis News. March 23, 1918, p. 16.

- “Marott Store Sold.” The Indianapolis Star. November 19, 1919, p. 17.

- Libby Cierzniak. https://historicindianapolis.com/indianapolis-collected-bringing-the-masses-to-mass-ave/ 2015.

- “Massachusetts Avenue Widening To Be Topic.” Indianapolis Star. October 14, 1928, p. 10.

- “Store Opening Attracts 40,000.” Indianapolis Star. July 26, 1929, p. 11.

- “Compromise On Costs.” Indianapolis Star. March 3, 1933, p. 6.

- Photo Credits: Pythian Building Indiana Album Evan Finch Collection; Marott Friends of Marott Woods; Marott Department Store. Indiana Album Evan Finch Collection; Forward Magazine Commercial Club of Indianapolis; Grand Spring Opening Indianapolis Star. April 11, 1911; Lou Cottingham Indianapolis Star. May 6, 1906; Draft Registration Indianapolis Star. August 30, 1948; Sears Opening Indianapolis Times. July 23, 1929.